Thousands of Singaporeans lent ears to Dr. Jane Goodall, renowned primatologist and UN messenger of peace, as she preached climate change actions in November 2019. At the same time, a 16-year-old girl shook national leaders awake from their inaction to keep global temperature rise below 1.5°C. In today’s age of information boom, scientific knowledge is no longer of scarcity or exclusivity: anyone with adequate training and knowledge is able to debate science. However, this empowerment proves a double-edged sword. Skeptics arm their confirmation biases with data, and fabricated claims are spread at the speed of light. Under such circumstances, what if any obligations do I still have to try to convince the skeptics?

The meaning of “obligation” is twofold: first of duties, and second of rights. While an obligation demands the obligor to perform, it bestows upon them the right to demand responses from the obligee, and vice versa.

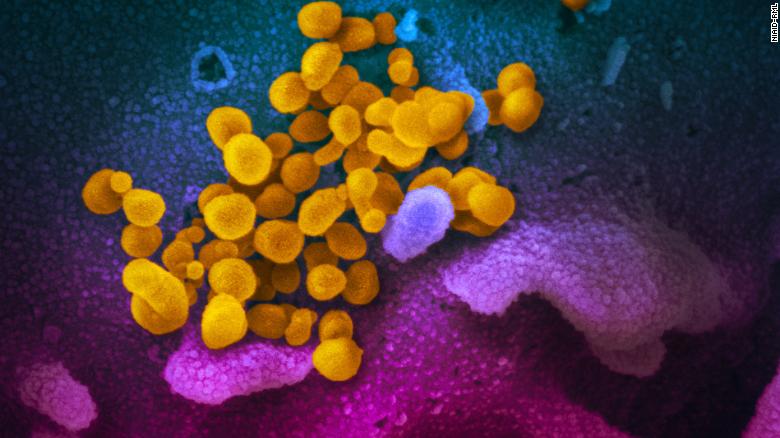

It is unquestionable that I, as a scientist-in-training, am motivated by the moral duty to communicate science. However, the further I went along this quest, the more doubtful I became. During the recent novel coronavirus pneumonia (NCP) outbreak originated in Wuhan, China, I suffered great pain seeing my family and friends collapsing under overwhelming information. No matter how hard I tried to explain new primary literature and virology principles, I could not dissuade my mother from believing in myths and conspiracy theories.

Gradually, I felt deprived of the right to change others’ beliefs in accordance with objective, empirical truths. On the one hand, the scientific method itself is riddled with subjectivity, and certainty is only a goal scientists strive for through repeated controlled experiments and peer review. On the other hand, stubborn advocacy could shatter audience’s web of beliefs and mental well-being. Seemingly, we are neither epistemically nor ethically justified to influence minds that are cognitively and emotionally reluctant to change.

In the grass-root organization I currently volunteer for during the same outbreak, the ripple effect of this moral duty disentangled my conflicted thoughts. Every young scientist and doctor in my group go to great lengths to discuss the veracity of new discoveries about the virus, and to convince those with doubts. What precedes moral duty is our shared intellectual responsibility to learn as we discover, and perform rational assessments of empirical findings. Above all, we are all stimulated by the spiritual calling from our nation in times of need. We are scholars before scientists, and citizens before scholars.

Check out our online aid website here.

Scientists have the obligation to advocate, not because we know, but because we are eager to know. Our intellectual and moral motivations are buttressed by regulations, shared practices and a community of support to maximise objectivity and universality of our knowledge about the natural world. Only under such a support system—social, economic, and legal— can we execute our duties to communicate science and our rights to demand skeptics to cooperate. Only then do we have the right to try to change their perspective and win their hearts.